- Home

- Simon Mitchell

The Fighting Stingrays Page 2

The Fighting Stingrays Read online

Page 2

Charlie stared at that photo a lot, not because it was the only picture of Johnny they had, but because he was pretty sure his parents hadn’t smiled like that since.

The Fighting Stingrays met underneath the big tamarind tree on Milman Street, like they did every morning. The tree’s sprawling branches and frond-like leaves provided a cool shelter from the morning sun, and its lumpy, sausage-shaped fruit was both sour and sweet – just the thing for a before-school snack.

Alf cast his eyes up and down the street before opening his palm to reveal a small brassy-looking bullet. ‘It’s a .303,’ he said. ‘Like our blokes use in their rifles. And look, it hasn’t been fired yet!’

Charlie and Masa gaped at the bullet in Alf’s hand. ‘Where’d you get it?’ Charlie asked.

Alf slipped the bullet into his pocket. ‘Found it,’ he said with a shrug. ‘Found a whole clip of them, actually.’

Charlie and Masa exchanged a look. They knew what ‘found’ meant. Alf was always pinching things – it was like he couldn’t stop himself. Every time he walked past an open window, or got handed the collection plate in church, he had to help himself to a little something. He’d been caught loads of times and his old man gave him plenty of wallopings for it, but that didn’t stop Alf. In fact, Alf was probably just following in his dad’s footsteps – nobody knew the whole story, but there were rumours that Alf’s dad had only come to TI to escape some sort of trouble with the cops back in Sydney.

Charlie raised an eyebrow at Alf. ‘Where’d you find it?’ he asked.

Alf grinned. ‘I went out for a stroll last night and came across a soldier fast asleep in the sand. He must’ve got tired on his way back to camp from the Federal and decided to take a little snooze. He’ll probably think he used up the clip shooting rats when he was stonkered.’

‘Shh,’ said Masa. ‘You’ll upset Judy.’ He pulled the rat out of his pocket and placed her gently on his shoulder. ‘Don’t worry. Nobody’s going to shoot you,’ he told her.

The Fighting Stingrays started trudging up the hill towards the school. ‘Are we going fishing this arvo?’ asked Masa, picking a piece of tamarind pulp out of his teeth.

‘Nah, I want to swim,’ said Charlie. He was terrible at tennis and football and basketball but was probably the best swimmer in the whole school. He could hold his breath under water for nearly three minutes – almost as long as the Islanders who dived for trochus shell in the shallows.

‘But Ginger caught an eighty-pound mackerel yesterday,’ said Masa.

Alf snorted. Eighty pounds? I saw that fish, and he was lucky if it was eighteen.’

‘I love mackerel,’ said Charlie.

‘Love it, do you?’ teased Masa. ‘Then why don’t you marry one?’

‘Gee, Masa, I would, but I’d always be worried you were going to take a bite out my wife, raw. Besides, as soon as I’m old enough I’m going to ask Rosie to marry me.’

‘What, your maid?’ said Alf. ‘But she’s . . . you know . . . coloured.’

Like a lot of people on TI, Rosie was a mix of races – her dad was Chinese, her mum was half Malay, and one of her grandparents was from Mer, an island way over the other side of the Torres Strait. Charlie wasn’t so sure about calling her coloured though – that made it sound like Rosie’s skin was bright blue or green, instead of a perfectly normal brown.

‘I don’t care,’ said Charlie. ‘I think she’s pretty.’ Masa agreed. ‘Too pretty for you. But you can marry my cousin, Kiyoko, if you want.’

‘Cripes, that’s very generous of you,’ said Charlie. ‘But I’d rather be married to a fish than a dragon.’

Masa’s dad, Mr Ueshiba (or Mr U as everyone called him), was lead diver on the Dolphin, one of Napier & Co.’s luggers. That meant he was often away for weeks at a time, sailing from one corner of the Strait to the other, collecting pearl shell. When they found a spot that looked promising, Mr U would put on a big round metal helmet, like something out of a Buck Rogers comic, and descend into the depths to pull the shell off the bottom. He had some incredible stories about strolling through coral gardens teeming with fish and uncovering shimmering new fields of pearl oysters at forty fathoms below the sea.

Everyone liked Mr U, which might have had something to do with his habit of buying a ginger beer for anyone who was in the general store when he went there. But Masa’s mum had died a long time ago, so whenever Mr U was out on the lugger, Masa had to stay with his Auntie Reiko and seventeen-year-old cousin, Kiyoko.

‘Auntie Reiko made me weed the garden at noon yesterday,’ Masa grumbled. ‘I nearly cooked! And she’s always threatening to drown Judy in the washing tub. Meanwhile, Kiyoko spends all day lazing around, reading romance novels in the shade and calling me her fat little dung beetle.’

Alf stifled a snigger. Masa’s relatives were horrible, but then again – living with Masa’s Uncle Jiro would turn anyone nasty. Jiro, who also dived from the Dolphin, was always in a bad mood, except when he had a bottle of whisky or rice wine in front of him. Even then, there was a fair chance he’d throw it at you once it was empty.

‘When’s your old man coming home?’ Charlie asked. His mouth was already dry from the walk up the hill, and one of Mr U’s ginger beers would go down very nicely.

‘No idea,’ said Masa. ‘All I know is your dad’s given them a pretty big target to make before cyclone season.’

‘Has your old man ever seen any Jap subs out there, Masa?’ asked Alf.

‘Any what?’ said Masa, giving him a dirty look.

Alf rolled his eyes. ‘Any Jap-a-nese subs?’

Masa shook his head. ‘Nah,’ he said. ‘But one of the divers from the Wanetta Company reckons he saw a periscope once. Mind you, it’s the same bloke who told me he kissed a mermaid.’

A couple of dark-skinned kids passed them, going in the other direction, and Charlie gave them a nod. There were three schools on TI – one for the white, Japanese and Chinese students, another one behind the tennis courts for the mixed kids and Malays, and a Catholic school up near the Torres Strait Hotel that was run by nuns.

Charlie, Alf and Masa didn’t have much to do with the mixed kids or Malays – they weren’t even allowed to play each other in sport. That was just the way things were, like how they had to sit in different parts of the picture theatre when there was a film on. They didn’t speak to the Torres Strait Islanders much either. Islanders weren’t usually allowed to live on TI, apart from the kids who stayed at the Catholic school and a handful of black soldiers stationed on the other side of Milman Hill. Even Bill, who worked for Charlie’s father as cook on board the Dolphin, had to spend most of his nights sleeping on the lugger when it was in port.

The government seemed to have an awful lot of control over the lives of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders – where they could and couldn’t live, who they were allowed to work for, how much they got paid and even who they could marry. It was all a bit unfair – Bill came from Badu, an island about thirty miles north of TI, and his people had been in the area for thousands of years before anyone else showed up. Surely the least they could give him was a proper bed.

The Fighting Stingrays slid to one side of the street as a bunch of soldiers jogged past, muttering to each other. Charlie overheard a couple of snippets of conversation: ‘On the wireless this morning . . . Hawaii . . . Manila . . . hundreds of planes.’ Ern was among the men, but he didn’t even glance in their direction.

‘Crikey, they looked awfully serious,’ said Alf once the small company had passed.

‘Yeah,’ says Charlie. ‘They’re probably after the mongrel who stole their mate’s bullets.’

‘Get out of it,’ said Alf, but he pushed the bullet deeper into his pocket, just in case.

It was like any other Monday morning at school – a bit of maths, a bit of history, a lot of straining to hear Miss Cassidy over the noise of the younger kids at the other end of the schoolroom. In fact, the only unusual thing that happened was when one of t

he stray goats that roamed the island wandered in and ate the orchids Miss Cassidy had in a vase on her desk.

But everything changed when they went home for lunch that afternoon.

They had reached the corner of Milman and Hargrave Streets when Charlie stopped in his tracks – a soldier was lying flat on his stomach in the Hockings family’s front yard, his rifle pointed straight at Yokohama. A few houses down, an Islander in army uniform was doing the same thing. Across the road, scores of khaki-clad soldiers were busily stretching out big coils of barbed wire.

‘Wha–what’s happening?’ said Masa, as an army truck rumbled past, its wheels sending up a big cloud of dust.

Ern was helping unroll the lengths of barbed wire. He jogged over when he saw the Fighting Stingrays on the other side of the street.

‘We’ve had some bad news, boys,’ he said, his mouth twisting. ‘Pearl Harbour was attacked this morning. Malaya and the Philippines too.’

‘Our pearling harbour?’ said Masa, gazing towards the line of luggers anchored just offshore, each one casting a perfect reflection in the still water beneath it.

‘No, you drongo,’ said Alf. ‘Pearl Harbour. It’s in Hawaii, isn’t it?’

Ern nodded glumly. ‘It’s where the Americans have a fair few of their warships. But Japanese bombers destroyed a big part of the fleet this morning, and thousands of people are dead. So now we’re at war with Japan as well as Germany.’

Charlie’s jaw dropped. The moment everyone had been expecting was finally here. Japan had launched a full-scale attack on a friend of Australia, and they probably weren’t going to stop there. He turned to face the channel between TI and Horn Island – what would it look like packed with Japanese warships?

Masa squinted at the mass of barbed wire around Yokohama. ‘So what’s all this for?’ he asked. ‘Keeping out the enemy if they come?’

Ern’s shoulders slumped. ‘Oh, strewth,’ he said. ‘I’m sorry, Masa, but we’ve got our orders – we’re supposed to round up every Japanese person on the island and keep an eye on them. You’re interned.’

‘What?’ exclaimed Charlie and Alf together.

Masa frowned. ‘Does that mean locked up?’

Ern nodded. ‘Pretty much.’

Charlie couldn’t believe it. ‘Ern, you can’t!’ he spluttered.

Ern rubbed his face. ‘Orders are orders,’ he said.

Masa stared at him for a moment. ‘But . . . I didn’t do any bombing,’ he said.

Ern sighed. ‘I know.’

‘I don’t reckon anyone else here did either,’ said Masa, sweeping one hand towards Yokohama. ‘Why are we getting locked up?’

‘Because you’re the enemy now,’ said Ern, swallowing hard.

‘But, I’ve never even been to Japan,’ pleaded Masa. ‘I was born right here on TI!’

‘I know,’ said Ern again, shifting from one foot to the other. ‘But your dad wasn’t. And according to the government that makes him the enemy.’

‘Dad . . .’ said Masa. ‘My dad’s out on the lugger. What’s going to happen to him?’

‘He’ll be interned as soon as he comes back in,’ Ern said.

‘But,’ Masa said, looking from Charlie to Alf to Ern and back to Charlie again. ‘But . . . but . . .’

This was ridiculous – there must have been some sort of mix-up. ‘Ern, Mr U’s been here for donkey’s years,’ Charlie said. ‘And Masa’s as Australian as any of us. Can’t you have a word to your boss or something?’

Ern opened his mouth to reply but was interrupted by a voice from across the road: ‘Private!’

Ern stood to attention as a tall soldier strode towards them. The man had small beady eyes, a neatly groomed moustache and short black hair, shiny with brylcreem, emerging from under his peaked cap. His socks were pulled up to his knees, his khaki jacket was immaculately pressed and the metal pips that decorated each shoulder were so highly polished that Charlie had to squint to look at them.

‘Private Riley,’ the officer snapped. ‘Why hasn’t this boy been interned yet?’ He had a high-pitched, slightly posh voice. He didn’t sound like he was from anywhere in Queensland.

‘Captain Maddox,’ said Ern. ‘I was just spelling out the situation to them, sir. This boy’s father is out on a pearling lugger, and I was explaining that we plan to –’

‘Explaining our plans?’ said Captain Maddox, his face going pink. ‘To an enemy alien?’

Ern opened and closed his mouth. ‘Nothing secret, of course,’ he said. ‘Besides, sir, he’s only a kid.’

‘Only a kid?’ Captain Maddox looked down at Masa like he was a blowfly that needed to be swatted. ‘All Japs are sneaky buggers, Private Riley, even the young ones. This sly little toad would slip into your tent and cut your throat in your sleep if you gave him half a chance.’

‘I would not!’ protested Masa.

‘He really wouldn’t,’ said Alf. ‘He can’t even gut a fish without feeling crook in the stomach.’

‘Shut it!’ roared Captain Maddox. ‘This little turd’s father is probably out there drawing up navigation charts for a full-scale invasion as we speak. Private, get this boy back inside Japtown quick smart. Otherwise you can personally explain to the Fort Commander why you’re fraternising with the enemy.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Ern, without much enthusiasm. He placed one hand on Masa’s shoulder. ‘Come on, mate.’

Masa’s chin trembled. He stared back at Charlie as Ern escorted him over the road and into Yokohama through a gap in the barbed wire. Charlie watched helplessly. Masa was a Fighting Stingray – he was supposed to be doing battle against the enemy, not locked up as one of them.

‘Excellent, that’s another one,’ murmured Captain Maddox, regarding the growing barbed wire fence with a smug smile.

Charlie cleared his throat. ‘Please, Captain Maddox,’ he said. ‘Masa’s our mate. He doesn’t know anything about navigation. He thinks the port side of a boat is where you keep your luggage.’

Captain Maddox snorted. ‘They’re all as bad as each other,’ he said. ‘Filthy, treacherous spies, the lot of them.’

‘But, what’s going to happen to him?’ Charlie asked.

A vein bulged in Captain Maddox’s neck. ‘You’re addressing an officer, boy,’ he said. ‘Call me “sir”.’

Charlie forced himself to look Captain Maddox in the face. ‘What will happen to Masa now, sir?’

Captain Maddox smiled and his small, gleaming eyes shrunk even further. ‘Your so-called friend is an enemy alien and a threat to the security of Australia. We will hold him here until arrangements are made to transport him to an internment camp on the mainland. After that, I suspect you will never see him again.’

The barbed wire going up around Yokohama wasn’t the only thing that changed over the next week. Army and navy men were suddenly racing around TI like termites on a timber verandah. The men were busy clearing scrub, hauling sandbags and digging trenches in the rocky ground. They even installed a couple of machine guns and searchlights at the corners of Yokohama in case any of the few hundred Japanese inside tried to make a run for it. Charlie and Alf got as close to the machine guns as they dared, admiring the thick black barrels and round magazines of bullets. They were magnificent-looking things – it was just a shame that they were pointed in the direction of their friend.

Whenever a pearling lugger came in, it was met at the dock by a party of soldiers. The Japanese crew members were marched straight along the shorefront and into the makeshift internment camp. But there was still no sign of the Dolphin, and Captain Maddox wasn’t the only one saying that Mr U had been spying for the Japanese Navy and was already on his way back to Tokyo to tell them the best way to take over the Torres Strait. But Charlie knew Masa’s dad would be busy making a big haul of shell at the Darnley Deeps.

A lot more local men started talking about joining the army or navy, a few of Napier & Co.’s Malay workers were worried about their relatives back home, and people of e

very colour laughed and smiled a lot less. But otherwise, life on TI pretty much went on as normal. Most of the hotels and shops stayed open. It was still swelteringly hot every day, and the horde of cats that lived in the Wanetta Company’s packing shed still stampeded down to the jetty when they heard the putt-putt of a boat coming back from a fishing trip. Everybody still had their baths in the ocean, but the Japanese were the only ones who had armed soldiers keeping an eye on them as they washed their hair in the salty water.

And the Fighting Stingrays still had to go to school. Even Masa didn’t escape that. Every morning, the soldiers standing guard would open a gate in the barbed wire fence and a handful of children would file out of Yokohama and head up the road to the schoolhouse. Charlie and Alf met Masa under the tamarind tree as usual, but there were no more fishing trips, or war games or swims in the sea baths – Masa had to go straight back to Yokohama every afternoon.

‘Honestly, I reckon Auntie Reiko’s even worse now,’ said Masa, as the three of them took the long way home after school one day, walking as slowly as they could to make the most of the few minutes before Masa went back through the gate into Yokohama. ‘Ever since the wire went up, all she does is clean. And guess who has to help her with the mopping and dusting? Meanwhile, Cousin Kiyoko’s started mooning over this army fella who’s been standing guard. Every day she puts on her best frock to go up to the fence and bat her eyelids at him like she’s Vivien Leigh or something. I bet the poor bloke didn’t think he’d have to face that kind of thing when he signed up.’

Charlie forced a chuckle. The Fighting Stingrays were acting like nothing was wrong, but everything was different now Japan was in the war. ‘Any word on when you’ll be going to the mainland?’

Masa shrugged. ‘There’s still too many luggers out. But Captain Maddox reckons it’ll be soon. He’s been skulking around Yokohama and reminding us every chance he gets.’

The Fighting Stingrays

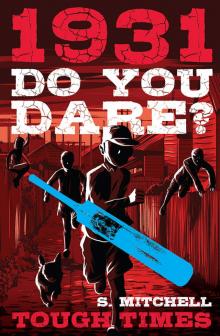

The Fighting Stingrays Do You Dare? Tough Times

Do You Dare? Tough Times