- Home

- Simon Mitchell

The Fighting Stingrays

The Fighting Stingrays Read online

About the Book

Charlie, Masa and Alf are best mates – loyal and adventurous. They’re the Fighting Stingrays.

In between school, swimming and fishing on idyllic Thursday Island, they have a ripper time role-playing bombing missions and other war games. But when Japan enters World War II, the Fighting Stingrays are told that one of their own is now the real-life enemy. Drawn into a dangerous game of cat and mouse in the Torres Strait, their friendship and loyalties are tested as the threat of invasion looms closer.

CONTENTS

About the Book

Map: Australia

Map: Torres Strait

Chapter 1 War Games

Chapter 2 Just Another Monday Morning

Chapter 3 The Bends

Chapter 4 A Yarn Through the Fence

Chapter 5 The Rescue Mission

Chapter 6 Cooped Up

Chapter 7 Spotlights and Gunfire

Chapter 8 The Zealandia Departs

Chapter 9 A Visit From Maddox

Chapter 10 Sitting Ducks

Chapter 11 A Close Shave

Chapter 12 Now What?

Chapter 13 All Aboard

Chapter 14 Charlie Jumps Ship

Chapter 15 Escape From TI

Chapter 16 Spotlights and Thunder

Chapter 17 Into the Drink

Chapter 18 Adrift

Chapter 19 Gecko Island

Chapter 20 Darwin

Chapter 21 Dark Times On A Tropical Island

Chapter 22 Unexpected Guests

Chapter 23 Holed Up

Chapter 24 Fire In Paradise

Chapter 25 Underwater Encounters

Chapter 26 More Visitors

Chapter 27 Welcome Home

Chapter 28 Captured

Chapter 29 Charlie’s Rope Trick

Chapter 30 Operation Maggot Squash

Chapter 31 The Battle Of Horn Island

Chapter 32 Heaven

Chapter 33 Bye Bye, TI

The History of Thursday Island

Acknowledgements

Also by Simon Mitchell

The plane’s engines screamed. Wing Commander Charlie Napier wrestled with the controls as anti-aircraft fire tore through the skies around him. ‘Hold her steady, fellas!’ he yelled. ‘We’re not dead yet. These Germans couldn’t hit the side of a hill from ten yards away.’

No sooner had he said it than an explosion erupted at the rear of the plane and the whole aircraft shuddered from nose to tail.

‘Everything all right, Sergeant Masa?’ Charlie called. Charlie might have been the first twelve-year-old to pilot a bomber in the Royal Australian Air Force, but he couldn’t do it without his two crewmates. Together they were the world-famous force the papers called the ‘Fighting Stingrays’.

‘Still here, sir,’ cried Masa Ueshiba, the tail gunner. ‘A bit of shrapnel hit us, but it’ll still fly. Uh-oh, Germans at eight o’clock!’ There was a burst of machine gun fire as Masa sprayed the enemy fighter planes with bullets. ‘Got ’em,’ he said. ‘All five hundred of ’em are heading straight into the sea!’

‘We’re approaching the target now,’ said Charlie, wiping the sweat off his forehead. ‘Ready, Alf?’

‘Ready, Charlie, I mean, sir,’ said Flight Officer Alf Hurley, peering through the bombsight. ‘It’s Hitler’s ship, all right – we can win the war right now if we sink it.’

‘When you’re ready then,’ said Commander Charlie, desperately trying to keep the plane steady as the damaged tail threatened to send them spiralling into the ocean.

Alf kept his eyes locked on the bombsight. ‘Three . . . two . . . one . . . bombs away!’

The three airmen held their breath as a hail of bombs fell towards the German ship. One of them exploded on the prow of the boat, while another one blew a massive hole in the main deck. Black smoke and debris went everywhere, and the Fighting Stingrays cheered.

‘Take that, you Nazi scoundrels!’ yelled Alf.

But then Adolf Hitler himself appeared on the deck of the ship, his moustache bristling with fury. ‘Oi!’ he roared. ‘What are you cheeky buggers up to now?’

The loud voice snapped Charlie back to reality. He skidded to a halt on the dusty road that ran along the Thursday Island waterfront. Behind him, Masa lowered his driftwood machine gun while Alf stood frozen, his raised hand clutching their next ‘bomb’ – a golf-ball-sized sea almond.

Charlie cleared his throat. ‘Sorry, Ern,’ he called. ‘We were just trying to sink Hitler’s battleship.’

The sandy-haired man in the short-sleeved army uniform grinned and pelted one of the thick-skinned green almonds back towards them. ‘I admire your guts, boys,’ Ern Riley said. ‘But I reckon Hitler’s probably got his hands full trying to take over Europe without coming down to TI, don’t you?’

Thursday Island, or ‘TI’, as everyone called it, was one of the smallest islands in the Torres Strait, the narrow, treacherous stretch of ocean and reefs that separated Far North Queensland from the wild jungles of New Guinea. Despite having the only proper town in the Strait, TI was as peaceful and beautiful as any of the area’s tropical islands, with bush-covered hills and sandy beaches where almond trees, coconut palms and wongai plums swayed in the sea breeze.

The Fighting Stingrays abandoned their bombing run and trudged through the stifling morning heat towards the jetty. The three of them were a mismatched bunch – Charlie was scrawny with pale yellow hair; while Masa was short and slightly chubby, his jet black hair always sticking up in one place or another. Alf was the giant of the group – even though he was only a year older than Charlie and Masa, he was almost as tall as a fully grown man, with big shoulders and ears that stuck out at right angles. Some people called him ‘Antenna Alf’ because of those ears, but only ever behind his back – you were in for a serious belting if you said it to his face.

The boys stopped in front of Ern, who stood guard next to a pile of wooden boxes at the end of the jetty. Masa rummaged around in his shirt and pulled out Judy, his brown-and-white pet rat. Officially, Judy lived in a box of straw in the Ueshiba’s house, but she actually spent most of her time curled up in one of Masa’s pockets or under his shirt. ‘Sorry, Judy,’ whispered Masa, placing her gently in the shade beside the stack of crates. ‘It’s too hot to have you running round in there today.’

‘You’re always whingeing about the weather,’ scoffed Alf.

‘You don’t like it either,’ retorted Masa. ‘You’re just too stupid to realise it.’

There was no such thing as a cool day on TI, but the build-up to the wet season was absolutely unbearable. The air was so thick with humidity it was like breathing warm custard and, even though it was early December, there was still no sign of the rains that would provide relief from the sweltering heat. To make matters worse, the island had completely run out of water, its reservoir and water tanks as dry as a dead skink’s tail. The Fighting Stingrays had to have their weekly baths in the sea, and all of their drinking water was brought in by ship, which meant they were only allowed a few gallons a day. Charlie could see why the native Torres Strait Islanders called the island Waiben, which meant ‘no water’.

Charlie wiped his forehead with the back of one arm. ‘What’s in the boxes, Ern?’ he asked, as a soldier hoisted another crate onto the pile and returned to the docked ship for more.

‘Guns?’ suggested Alf.

Ern shrugged.

‘Hand grenades?’ asked Charlie.

Ern winked. ‘That’s top secret, mate.’

Charlie’s, Alf’s and Masa’s mouths all dropped open at once.

‘It is hand grenades,’ said Masa.

‘Give us a look?’ asked Charlie.

Ern had lived a couple of houses down from Charlie’s family before joining the army, and he was usually happy to stop for a chinwag with the three boys. He glanced around to check if anyone was watching, but the only sign of movement was at the other end of the jetty, where a group of men dressed in khaki were rolling something down the ship’s gangplank.

‘All right,’ Ern said. He picked up a crowbar and prised the top off one of the boxes. Charlie leaned forwards as Ern reached inside and pulled out a large blue-and-white packet labelled ‘Bushells’.

‘Tea!’ snorted Alf.

‘Where are the grenades?’ asked Charlie.

Ern dropped the packet of tea back into the wooden crate and replaced the lid. ‘You can win a war without hand grenades,’ he said. ‘But if your soldiers don’t have any tea, you might as well run up the white flag straightaway.’

When the war had started a couple of years ago, things hadn’t changed much on TI. A few men had left to battle the Germans and the Italians in Greece or North Africa, but everybody else just got on with their business. After all, the fighting was a long way away.

But that had all changed in the past year or so as more and more Aussie troops arrived in the Torres Strait. They’d set up a navy base on nearby Wednesday Island, a huge searchlight on Goode Island and an airstrip on Horn Island, the island across the channel east of TI. Army men watched the surrounding waters from gun emplacements among the trees and termite mounds of Milman Hill, while a small city of tents had sprung up at the bottom of the slope. Meanwhile, the old underground fort at the other end of TI had been transformed into a military radio station. The number of dances at the town hall had tripled, and every night noisy soldiers and sailors filled the bars of the Grand Hotel, the Federal and the Metropole, spilling off the verandahs and into the dusty street, a glass of beer in one hand and a rolled cigarette in the other. The place was definitely living up to its other nickname – Thirsty Island.

But these men weren’t here to fight the Nazis – they were getting ready to fight the Japanese. From what Charlie could gather from his dad’s newspapers and the other kids at school, Japan had been making all sorts of noise about taking over Asia and the world. And because TI was at the very top of Queensland, closer to Port Moresby in New Guinea than to Cairns, it was one of the first places the Japanese would attack if they decided to invade Australia.

Charlie had heard terrible things about the Japanese – that they massacred women and children, enslaved the people they captured and tortured or even ate their enemies. Those stories might be true, but they didn’t really fit with Masa, or Masa’s dad or the hundreds of other Japanese people who lived in Yokohama, the cluster of boarding houses and shops near Charlie’s father’s warehouse. Masa sounded just as Australian as Charlie or Alf did, and Charlie had certainly never seen him eat anyone. Although Masa did eat a few pretty strange things, like raw fish, and sea cucumber soup, and soy sauce from Mr Yamashita’s little factory, which was so salty it almost took the skin off your tongue.

‘I’d like to see the Japs try and come to Australia,’ Alf said. ‘My brother’ll send ’em running like a goanna up a gum tree.’ Alf was always going on about his older brother, who was stationed at the air force base in Darwin. He was a mechanic, carrying a greasy wrench instead of a gun, but that didn’t stop Alf from acting like his brother was going to win the whole war on his own.

Masa glared at him. ‘Shut up, Alf. I told you not to say that word.’

‘What, “Jap”?’ said Alf. ‘It’s short for Japanese, isn’t it? I don’t care if you call me an “Aus”.’

‘Ass, more like it,’ muttered Masa.

But Alf wasn’t listening. ‘And if they do come to TI, we’ll be waiting for them.’ He held up an imaginary machine gun and fired it round in a circle, making a rat-tat-tat noise. ‘Right, Charlie?’

‘Too right,’ said Charlie. He was already marking off the years until he was sixteen so he could pretend to be nineteen and join up to fight. The newsreels that played before the Saturday night film at Thursday Island’s little open-air picture theatre showed all the fun the Australian soldiers were having overseas – smiling underneath their slouch hats, raising a flag over a conquered fort and racing their tanks across a far-off desert as dramatic music swelled through the speakers and flying foxes swooped in front of the screen. It was going to be a fantastic adventure – just so long as the Aussies didn’t smash Hitler and Emperor Hirohito so fast that the Fighting Stingrays missed out on the fun.

‘Coming through.’ A deep voice made Charlie jump. Masa made a lunge for Judy and stuffed her into his shirt as two soldiers lugged an enormous roll of barbed wire off the jetty and along the dirt road towards town, sweating and grumbling like a pair of angry boars.

‘What’s all the wire for?’ asked Charlie.

Ern swallowed hard. ‘Nothing,’ he said, his mouth tight at the corners.

Charlie sat on the side of his bed, rubbing his eyes. He’d barely got any sleep – at this time of year the fan on his ceiling just pushed the hot air around a bit, without actually cooling it down. But the heat wasn’t the only reason he was exhausted – he’d been up until well after midnight, reading Biggles Flies East yet again. Charlie loved the books about Biggles, the brave British fighter pilot who could shoot down half-a-dozen German planes, dodge non-stop anti-aircraft fire to rescue a crashed comrade, blow up an enemy ammunition dump and still be back at the aerodrome in time for dinner.

Charlie yawned, leapt up and changed into his school clothes. Then he half-straightened his sweat-stained sheets and plodded out into the hallway. The Napiers’ house was a large wooden building on stilts, with an enclosed verandah and a huge garden of fruit trees and flowers (although recently a few trees had been ripped out to make room for their underground air-raid shelter). It was one of the finest houses on the island, but the never-ending cycle of wet and dry seasons meant that it was always warping and moving about, and the floorboards in the hall creaked under every one of Charlie’s steps.

Rosie, the maid, was dusting the top of the piano when he appeared in the lounge. ‘Good morning, Master Charlie,’ she said.

‘Morning, Rosie,’ Charlie said. ‘I’ve got a new one for you – why did the chicken cross the sea?’

Rosie stopped dusting and looked at him. ‘No idea,’ she said. ‘Why?’

‘To get to the other tide,’ said Charlie, chuckling. Rosie shook her head, laughing. ‘Charlie, that is awful.’

‘You’re awful,’ said Charlie.

Rosie pretended that she was about to cry.

‘Awful nice!’ said Charlie.

Rosie whacked him on the top of the head with the feather duster. ‘Cheeky,’ she said. ‘Go, eat your breakfast and leave me in peace.’

Charlie took a seat at the breakfast table next to his little sister, Audrey, who was slurping on a big ripe mango from the tree in their backyard. She beamed at Charlie, her face covered in sticky juice and bits of pulp.

‘Crikey, just look at you,’ said Charlie, leaning over to wipe her face.

‘Shush, children,’ said Charlie’s mum, holding a wet towel over her forehead. ‘Bridge finished rather late last night, and I have a dreadful headache this morning.’

Bridge, bridge, bridge – it was all his mum ever did or talked about. Six nights a week, after eating the dinner Rosie cooked, Mrs Napier put on one of her nice dresses and drove the hundred-odd yards to the Langleys’ or the Kents’ or some other family’s house to spend the evening sipping gin and slapping cards down on a table.

Charlie’s dad flipped a page of his Courier-Mail. The newspaper was three weeks old, but it was brand new by TI standards, having only arrived on the boat from the south a few days ago. BOLD TALK BY JAPAN ON EVE OF NEGOTIATIONS screamed the headline on the front page.

‘Anything interesting in the paper today, Father?’ asked Charlie, tucking into the pieces of toast with vegemite Rosie had left on his plate.

Mr Napier turned anot

her page. Charlie hardly ever got to see his dad’s face when he was at home. If it wasn’t hidden behind a newspaper, then it was buried in a stack of accounts from Napier & Co. Pearl Shell Company.

Pearl shell – the gleaming, silvery-white inside of the enormous oysters found in the Torres Strait – is what brought people to TI from all over the world. Nearly all the island’s pearl-shell divers were Japanese, but any given day you would also find Malay deckhands, Chinese shopkeepers, Indians, Aborigines, Torres Strait Islanders and even the odd American there to buy up the heavy crates of pearl shell and ship them to the other side of the world to be made into buttons. There were a couple of thousand people living on TI, but only a few hundred of them had white faces like Charlie, and sometimes it was hard to believe the island was part of Australia at all.

Pearl shell had filled the harbour with double-masted pearling luggers and built the sprawling mass of warehouses, hotels and vine-covered wooden houses that straggled up the hillside like a battalion of badly trained soldiers. It was also what had made Charlie’s father one of the richest people on TI.

Charlie coughed. ‘I came second top in geography last week,’ he said. ‘Miss Cassidy reckons I was the only one who knew the capital of Abyssinia.’

Mr Napier flicked another page, his fingers stained grey from the newspaper ink running in the heat. Charlie’s mother rubbed her temples.

Charlie glanced at Audrey, who shrugged. He turned back to his parents. ‘Ginger Bowen caught an eighty-pound mackerel yesterday,’ he said. ‘He reckons he fought it for twenty minutes before it –’

‘Shhh!’ hissed his mother.

His dad’s newspaper finally jerked down. ‘Be quiet,’ he snapped, glaring at Charlie through his reading glasses. ‘Your mother’s not feeling well, and four of my divers have disappeared back to Japan in the last two weeks. We don’t have time for any of your nonsense.’

Charlie stared down at his plate. ‘Yes, Father,’ he whispered.

Charlie hadn’t always been the oldest. His brother, Johnny, died of polio when Charlie was four. Charlie barely remembered him, but the framed photograph on the sideboard showed a happy, confident boy of about thirteen standing on a beach and holding up a trumpet-shaped shell almost as long as his arm. Mr and Mrs Napier stood on either side of him, barefoot and smiling.

The Fighting Stingrays

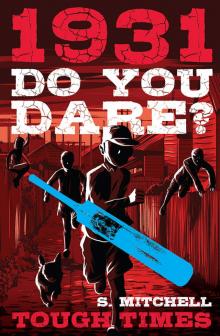

The Fighting Stingrays Do You Dare? Tough Times

Do You Dare? Tough Times